ERGEBNISSE VON IBISURVEY

letzte Aktualisierung: 04/07/2025

Anzahl der Beobachtungen

Anzahl der Teilnehmer

Anzahl der exotischen Vogelarten

Top 10 der gemeldeten Arten

- 523| Halsbandsittich (Psittacula krameri) 22%

- 280| Nilgans (Alopochen aegyptiaca) 12%

- 238| Pharaonenibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus) 10%

- 172| Sonnenvogel (Leiothrix lutea) 7%

- 159| Kanadagans (Branta canadensis) 7%

- 157| Mönchssittich (Myiopsitta monachus) 7%

- 91| Mandarinente (Aix galericulata) 4%

- 88| Wellenastrild (Estrilda astrild) 4%

- 85| Jagdfasan (Phasianus colchicus) 4%

- 55| Haubenmania (Acridotheres cristatellus) 2%

Interaktionen für alle exotischen Vogelarten

Anzahl der Beobachtungen nach Ländern

- 606| IT 26%

- 557| PT 24%

- 295| ES 13%

- 227| UK 10%

- 214| FR 9%

- 172| DE 7%

- 64| NL 3%

- 44| CH 2%

- 44| TR 2%

- 24| BE 1%

- 24| PL 1%

- 19| GR 1%

- 10 | RS 0%

- 10 | SE 0%

- 5 | HR 0%

- 5| LU 0%

- 5 | RO 0%

- 4 | AL 0%

- 4 | DK 0%

- 4 | SK 0%

- 3| AT 0%

- 3| ME 0%

- 2| AZ 0%

- 2 | BG 0%

- 2| CZ 0%

- 2 | NO 0%

- 1 | CY 0%

- 1 | FI 0%

- 1| HU 0%

- 1 | IE 0%

- 1 | RU 0%

- 1 | VA 0%

Haben Sie eine exotische Vogelart in freier Wildbahn gesehen?

Welche Verhaltensweisen haben Sie beobachtet?

Vögel zeigten Brutverhalten

Vögel zeigten andere Verhaltensweisen

Schicken Sie uns Ihre Beobachtung!

Schicken Sie uns Ihre Beobachtung!

› mit Fotos: Google-Konten | anderen Konten

› ohne Fotos

Vielen Dank für Ihre Teilnahme!

Das Projekt

Einführung

Seit der Antike werden zahlreiche Tier- und Pflanzenarten über ihre natürlichen Verbreitungsgrenzen hinaus transportiert, z.B. zur Produktion von Rohstoffen (z. B. Lebensmittel, Holz), Jagdzwecken oder als Zierarten. Teilweise führen diese Transporte dazu, dass Arten absichtlich in die Wildnis entlassen werden oder versehentlich entkommen. Wenn eine solche Art in einem Land oder einer Region nicht heimisch ist, wird sie im neuen Gebiet als exotisch oder gebietsfremd bezeichnet. Ein kleiner Teil dieser eingeführten, gebietsfremden Arten findet im neuen Gebiet geeignete Bedingungen vor, um sich anzusiedeln und zu vermehren sowie ohne menschliches Eingreifen einen Etablierungsprozess einzuleiten. Ein noch kleinerer Teil dieser etablierten Arten kann sogar invasiv werden, wenn ihre Individuenzahl steigt und sie sich über das Gebiet der Einbringung hinaus verbreiten, was negative Auswirkungen auf Umwelt, Landwirtschaft, menschliche Gesundheit oder Wirtschaft zur Folge haben kann.

Herausforderungen

Die Auswirkungen von exotischen Arten sind schwer zu beurteilen, wenn Daten zu ihrer Verbreitung, Häufigkeit und ihrem Verhalten nicht systematisch erhoben werden.

Weiterhin sind exotische Arten den meisten Bürgern möglicherweise unbekannt, da sie in populären Vogelführern häufig nicht aufgeführt werden, auf eine bestimmte Region beschränkt sind oder mit einheimischen Arten verwechselt werden.

Ziele

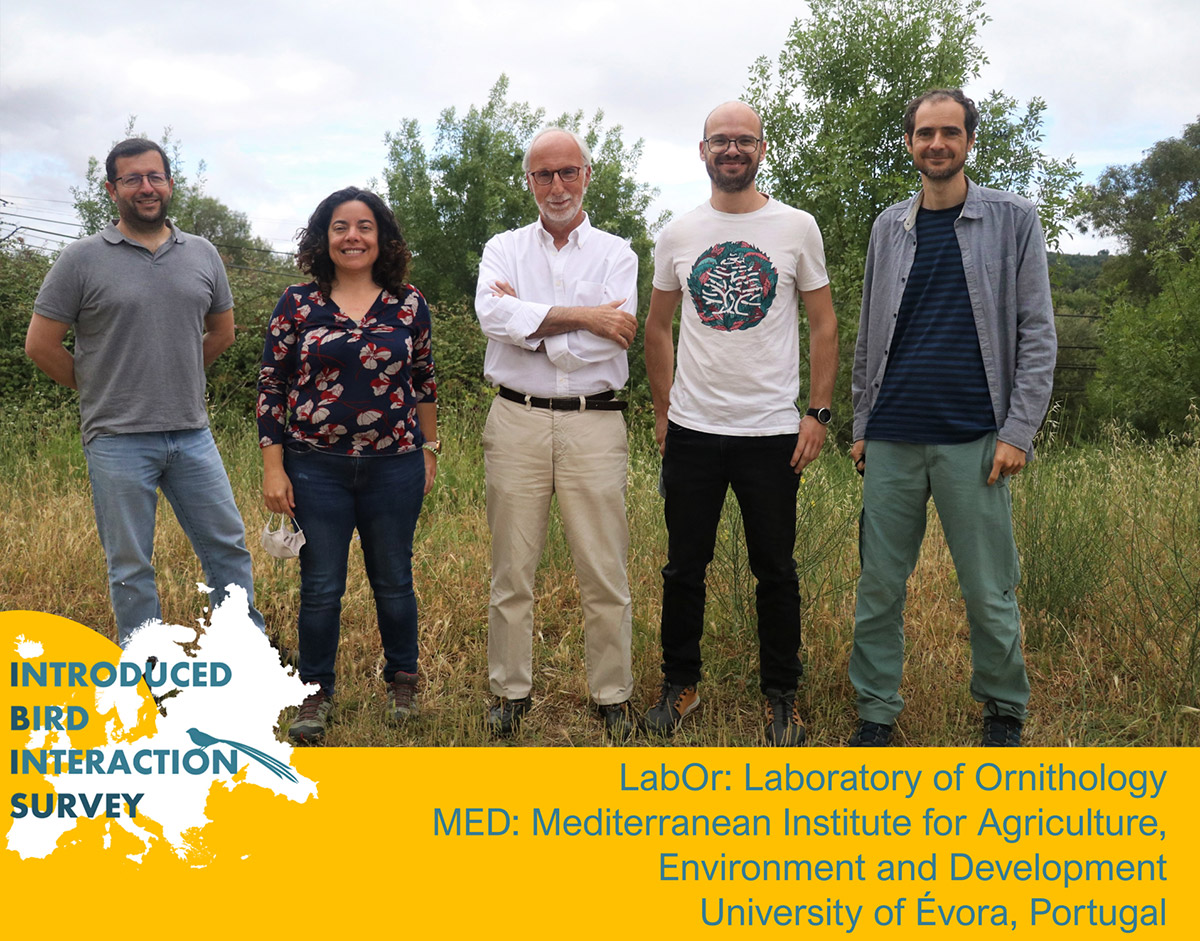

Die Umfrage zum Verhalten exotischer Vögel (engl.: Introduced Bird Interaction Survey – IBISurvey) ist ein Citizen-Science-Projekt von der Universität von Évora (Portugal) mit dem Ziel, die ökologischen, gesellschaftlichen und wirtschaftlichen Auswirkungen von eingeführten Vogelarten in europäischen Ländern zu bewerten. Der Schlüssel zur Beurteilung dieser Auswirkungen liegt hierbei in der Meldung des Verhaltens der eingeführten Vögel, beispielsweise dem Fraß von landwirtschaftlichen Nutzpflanzen oder dem aggressiven Verhalten gegenüber einheimischen Arten. Insbesondere zielt dieses Projekt darauf ab (1) die Bestimmung eingeführter Vogelarten für die breite Öffentlichkeit zu erleichtern, (2) Informationen über die Verbreitung, Häufigkeit und dem Verhalten von eingeführten Vogelarten zu sammeln und (3) das öffentliche Bewusstsein für die Auswirkungen von eingeführten Arten zu stärken.

Die Umfrage

Mit der Umfrage zum Verhalten exotischer Vögel regen wir Bürger dazu an, uns Interaktionen zwischen eingeführten Vogelarten und anderen Tieren, Pflanzen oder Menschen zu melden. Beobachter können alle exotischen Vogelarten melden, die in Europa eingeführt und in freier Wildbahn beobachtet wurden, indem sie den Artnamen eingeben oder eine Art aus einer Liste der am häufigsten beobachteten Arten auswählen. Darüber hinaus sind auch Meldungen von europäischen Arten, die in Länder eingeführt wurden, in denen sie natürlicherweise nicht vorkommen, möglich und willkommen.

Ihre Mithilfe ist enorm wichtig für uns, weil wir damit herausfinden können, welche eingeführten Vogelarten invasiv werden und somit unsere Einschätzung über ihre ökologischen, gesellschaftlichen und wirtschaftlichen Folgen verbessern können. Beispielsweise können die Ernährungsgewohnheiten eines eingeführten Vogels negative Auswirkungen auf landwirtschaftliche Nutzpflanzen haben oder zu einem Wettbewerbsvorteil gegenüber einheimischen Vogelarten führen. Auch die Meldung des Brutverhaltens von Individuen ist wichtig, um die Ansiedlung oder den Etablierungserfolg einer Art zu bestimmen. Die Angabe der Jahreszeit, des Lebensraums oder des Brutgebiets hilft, das Wissen über die Ökologie der Art im neuen Gebiet zu erweitern und ist wichtig, um den aktuellen Forschungsstand zu verbessern oder wirksame Managementpläne zu erarbeiten.

Zielarten: Eingeführte Vögel (oder deren Nachkommen), die in freier Wildbahn an einem Ort beobachtet wurden, an dem sie mit menschlicher Unterstützung ankamen.

Keine Zielarten: Vögel, die in Gefangenschaft beobachtet wurden, wie z. B. in Käfigen (flugfähige Vögel) und Umzäunungen (flugunfähige Vögel) von zoologischen Gärten.

IBISurvey ist Partner des Europäischen Informationsnetzes für gebietsfremde Arten (EASIN).

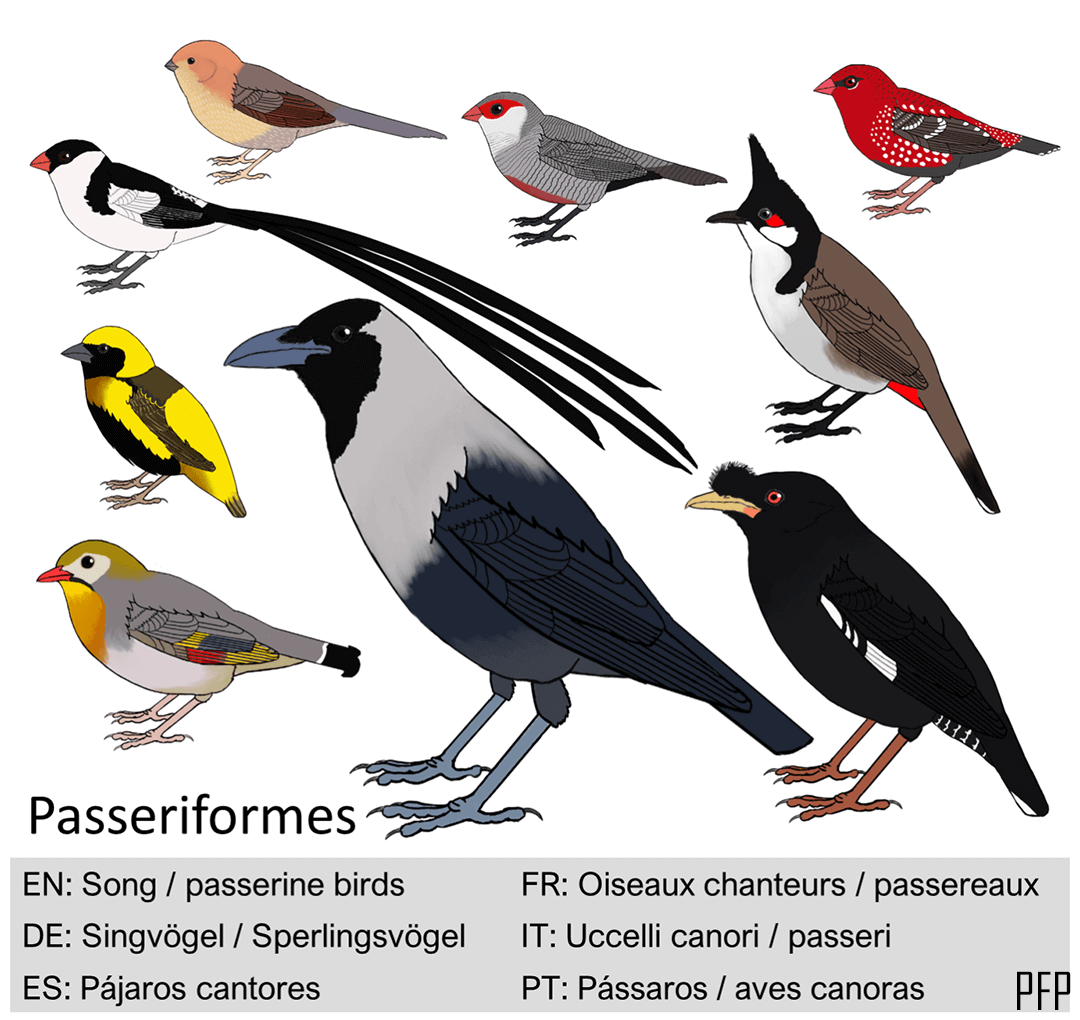

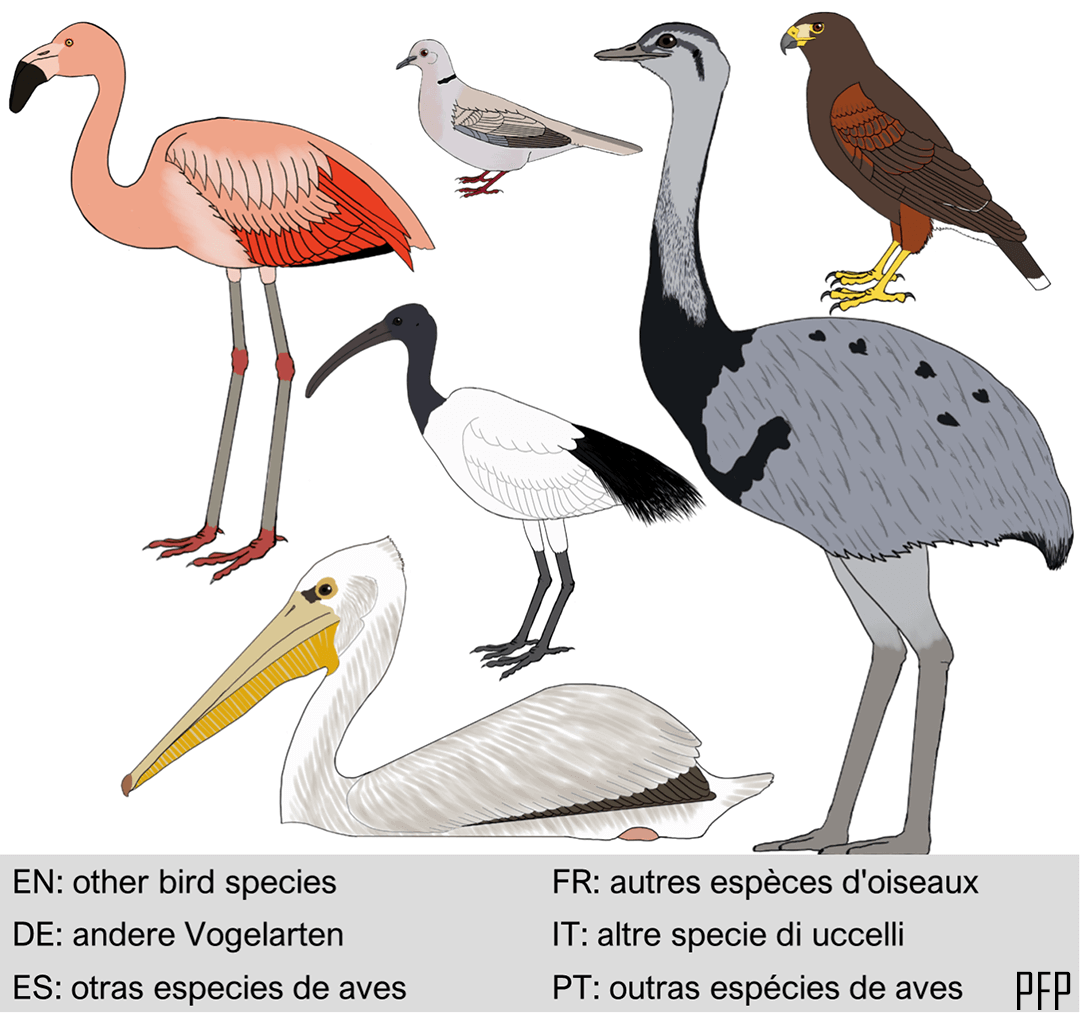

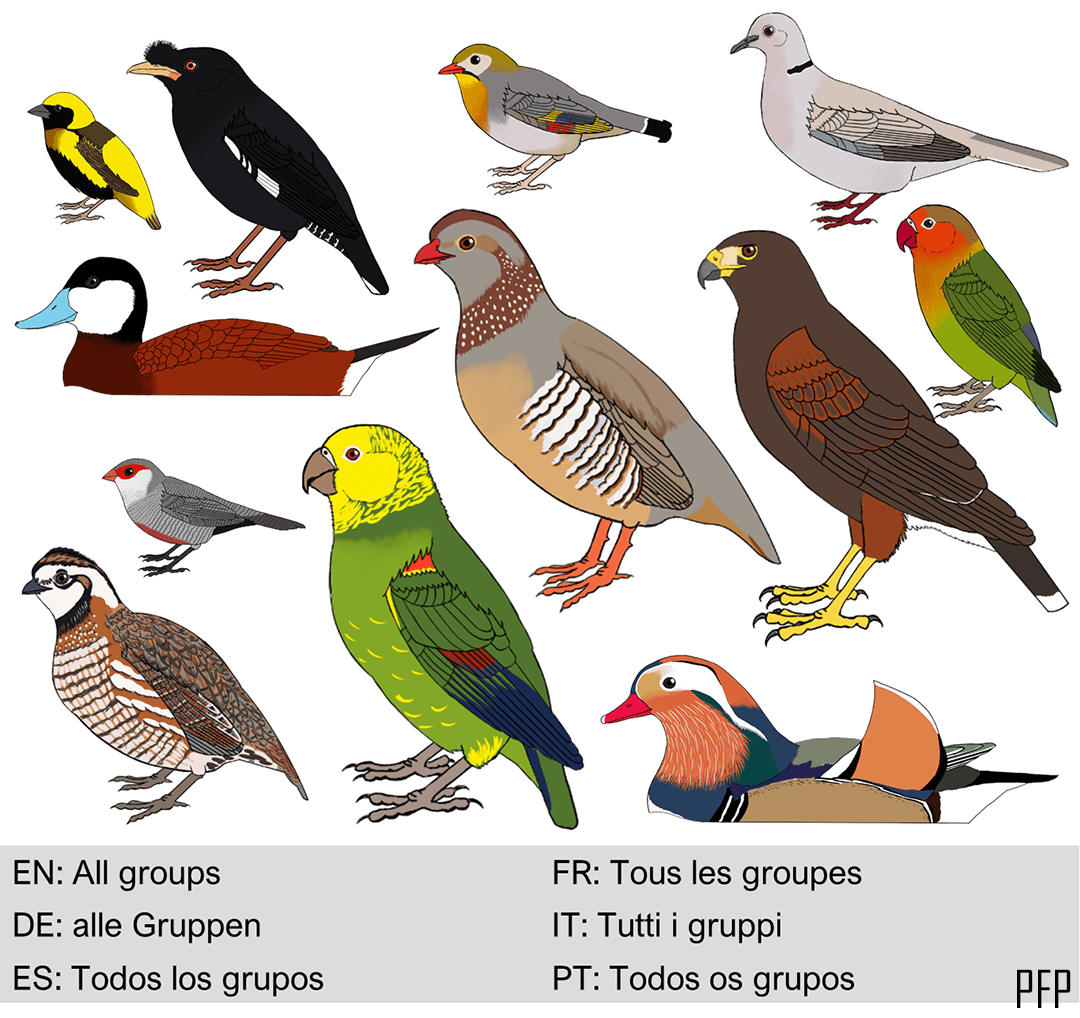

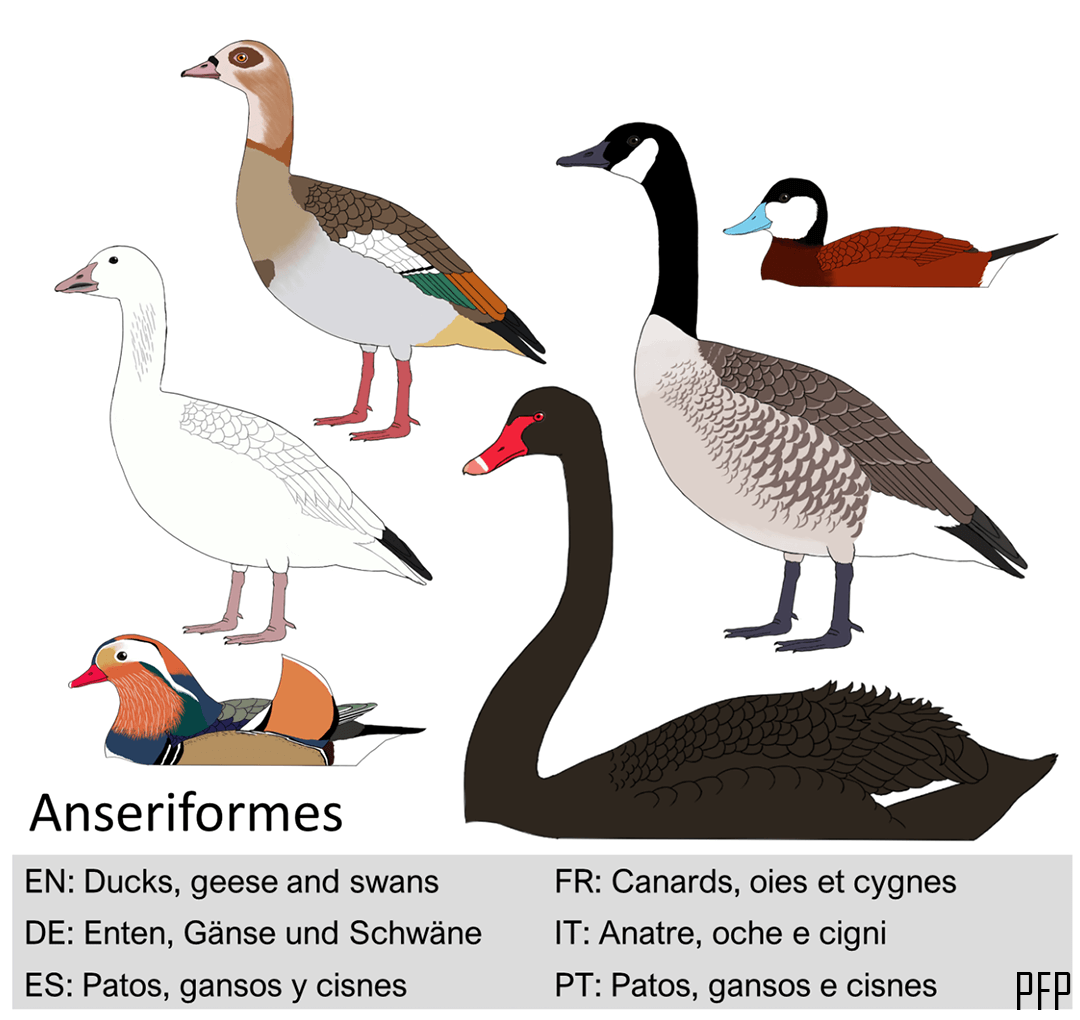

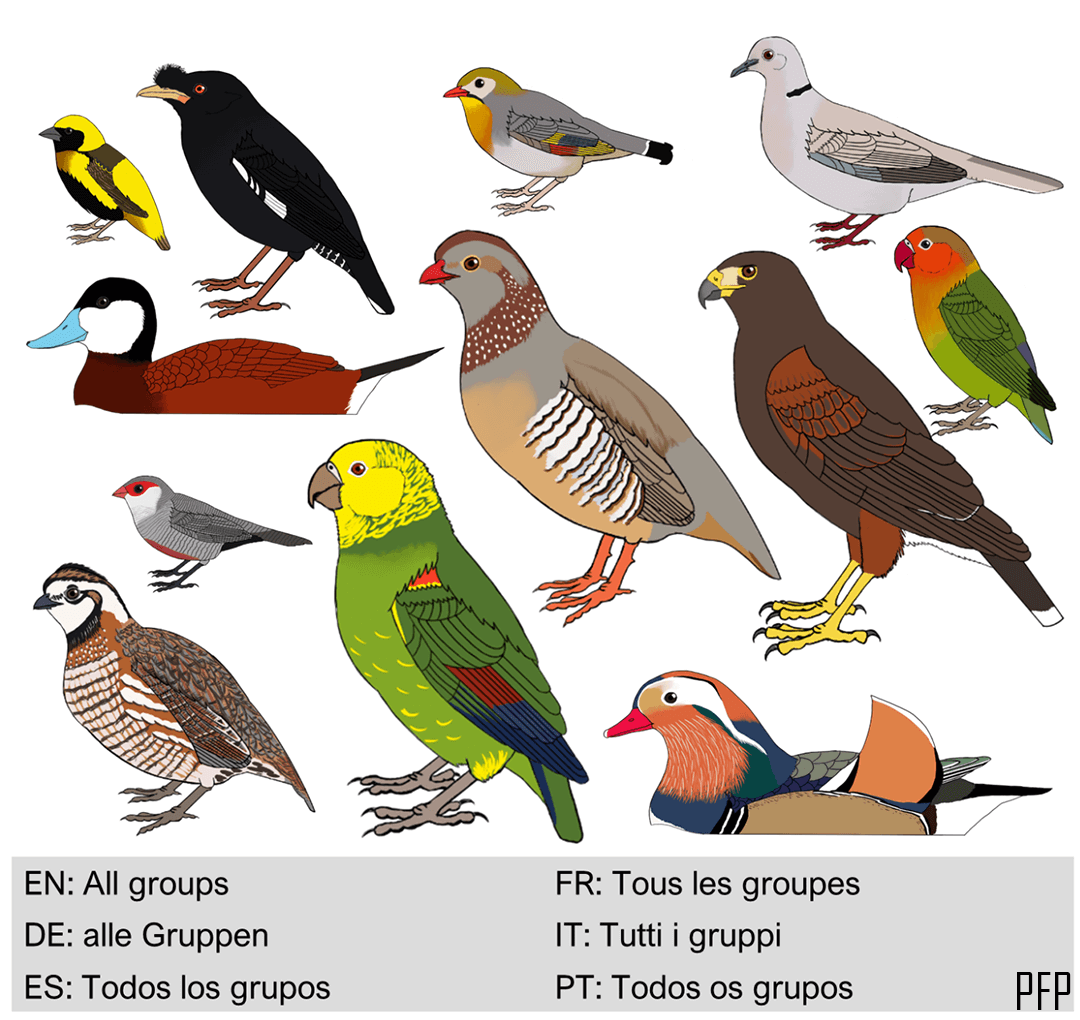

Artenblätter

Wir haben Fact-Sheets für exotische Vogelarten erstellt, die (1) erfolgreich in Europa eingeführt wurden (etablierten Arten), oder (2) häufig in freier Wildbahn beobachtet werden, jedoch ohne bekannte etablierte Populationen zu haben. Das Artenblatt zeigt (1) Bestimmungsmerkmale anhand des Gefieders und vergleicht es mit ähnlichen Arten, (2) die Ökologie der Art und (3) den aktuellen Status der Ansiedlung der Arten in allen europäischen Ländern und Regionen auf.

Im Hinblick auf das Gefieder können drei Typen dargestellt werden: (1) Wildtyp: Gefieder, das natürlicherweise in Individuen des Herkunftslandes vorherrscht; (2) domestizierter Typ: Gefieder, das aus menschlicher Selektion und Zucht resultiert; (3) Hybrid: Gefieder, das aus der Kreuzung verschiedener Arten resultiert. Für domestizierte Typen und Hybriden werden nur die häufigsten Beispiele gezeigt.

Der Status der Arten in Europa wird ständig aktualisiert, da immer wieder Vögel entkommen oder eingeschleppt werden oder weil der Etablierungsprozess einige Zeit in Anspruch nimmt. Möglicherweise gibt es auch eingeführte Populationen, die noch darauf warten, entdeckt zu werden.

Um zu erfahren, wie man eine in Europa eingeführte Vogelart bestimmen kann, klicken Sie hier:

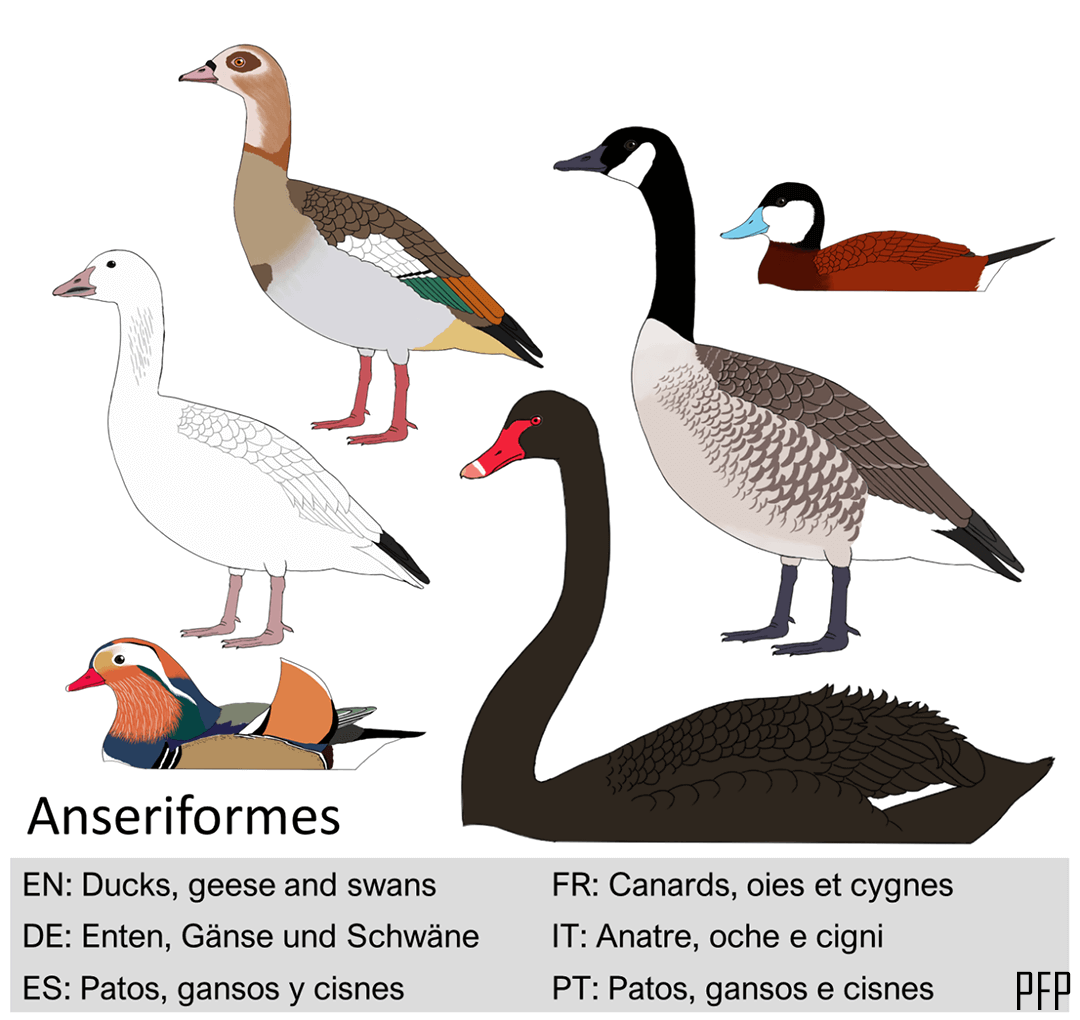

Enten, Gänse und Schwäne (Anseriformes)

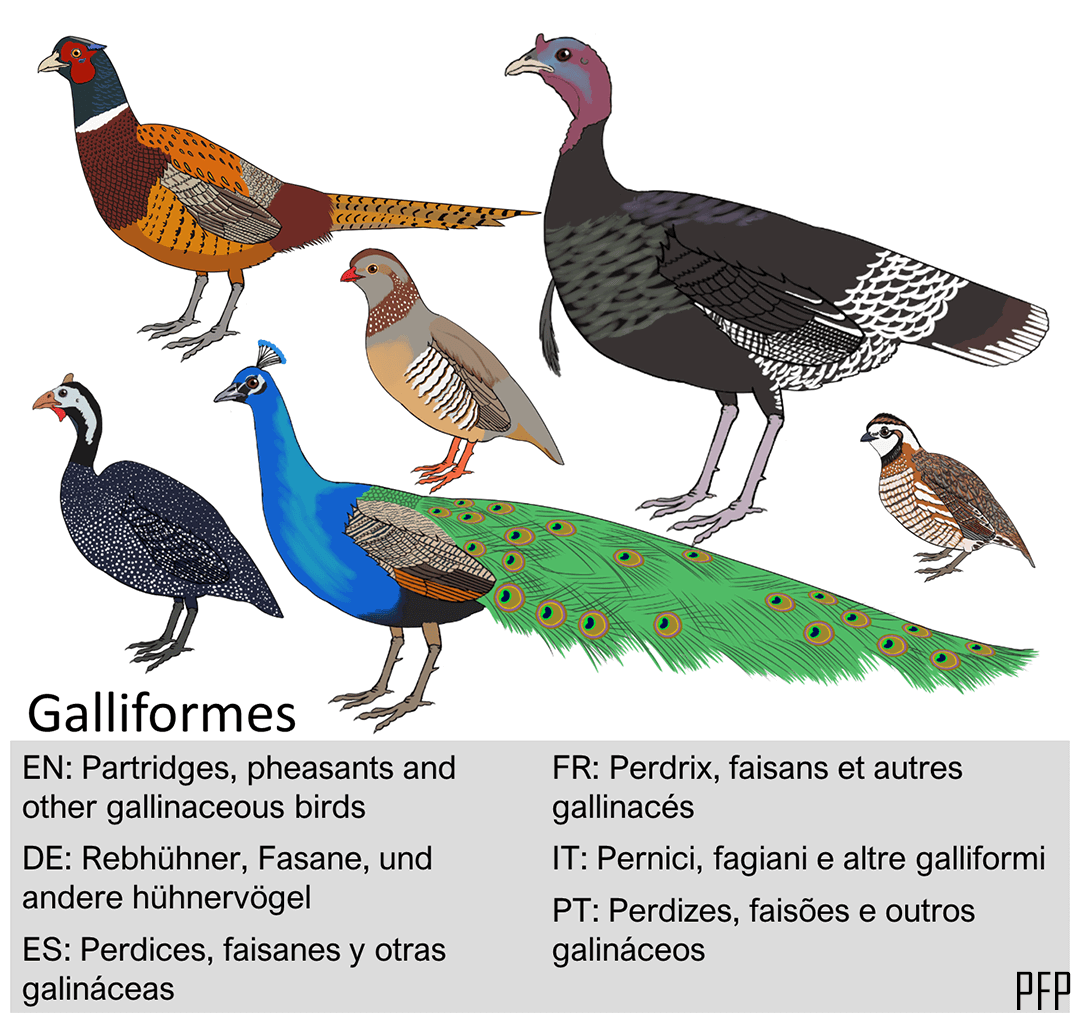

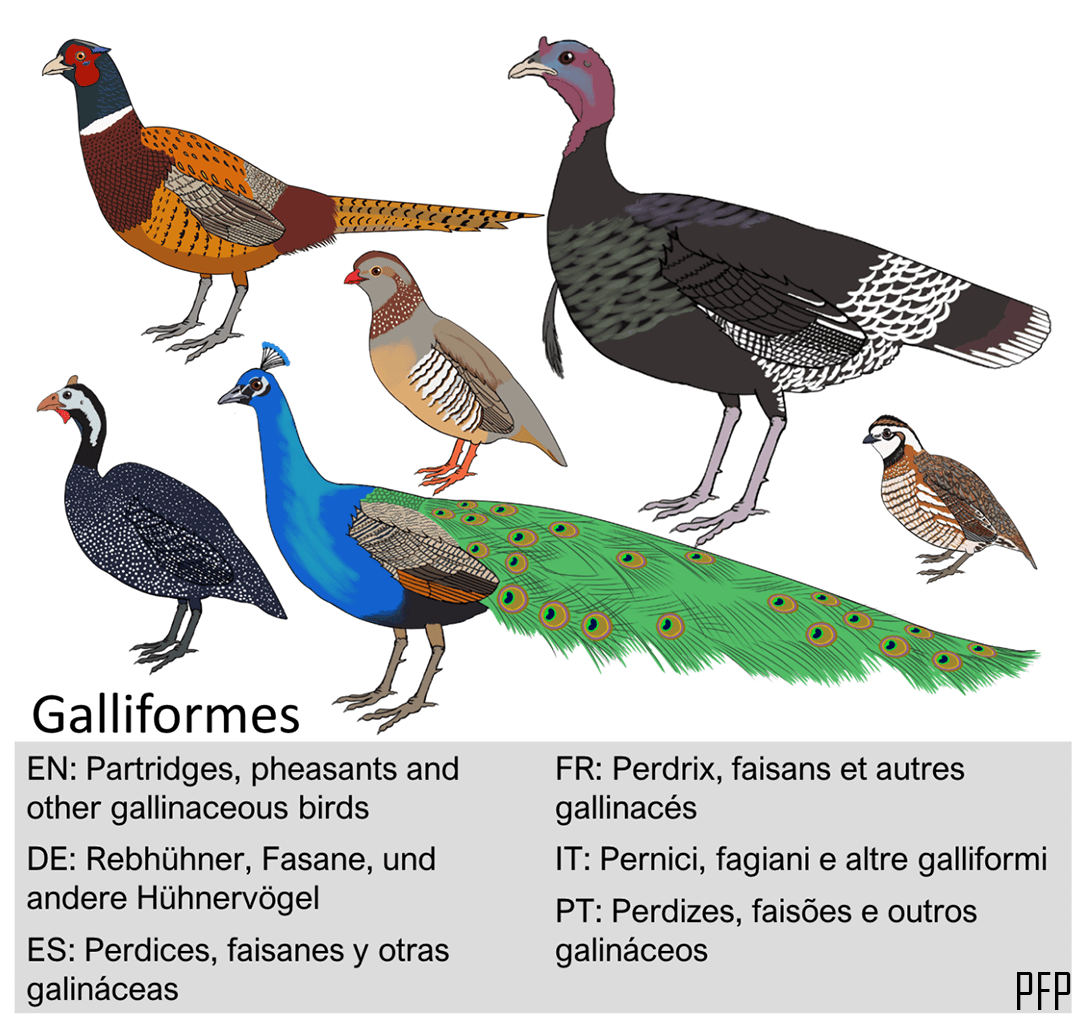

Rebhühner, Fasane, und andere Hühnervögel (Galliformes)

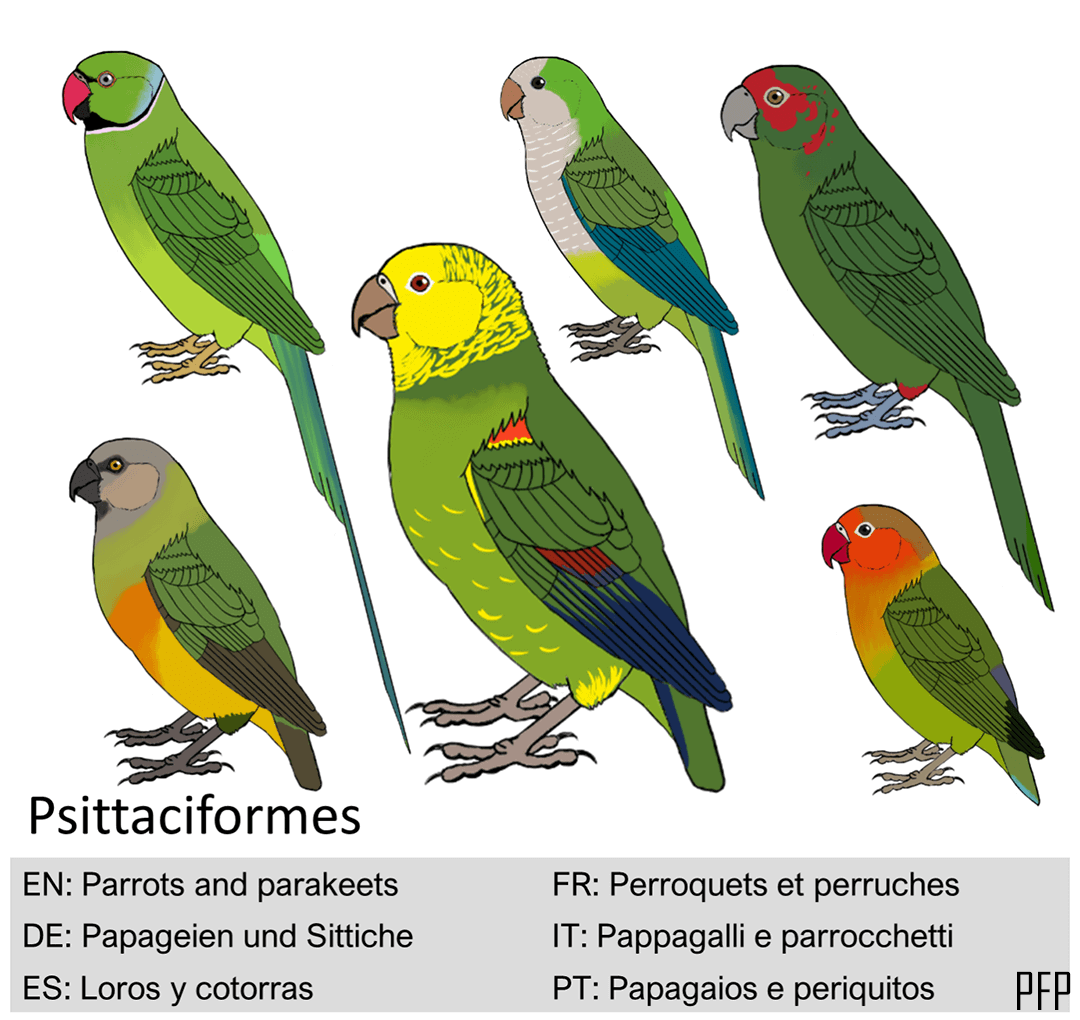

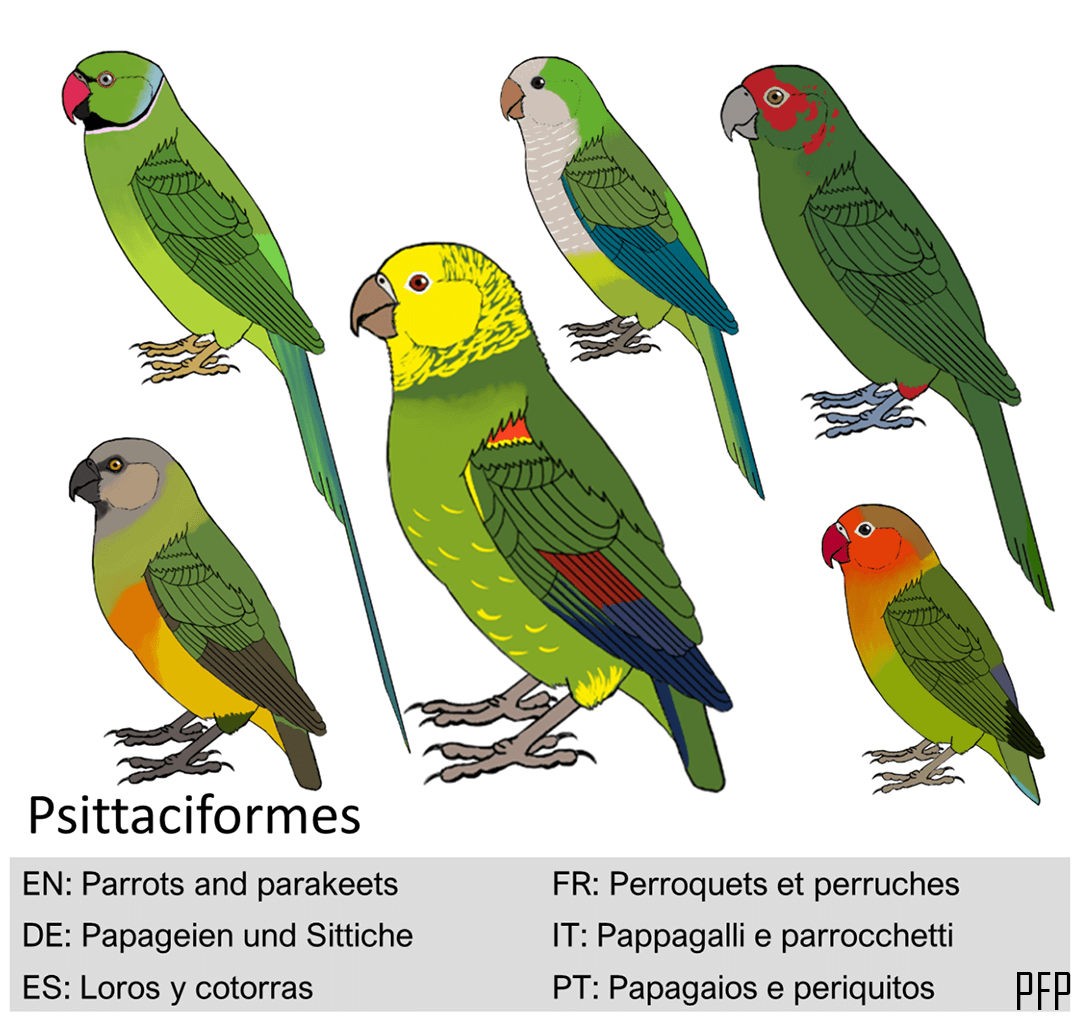

Papageien und Sittiche (Psittaciformes)

Referenzen und wichtige Links

Taxonomieund Nomenklatur:

Barthel, P. H. & T. Krüger (2019): Liste der Vögel Deutschlands. Version 3.2. Deutsche Ornithologen-Gesellschaft, Radolfzell.

Gill F, D Donsker & P Rasmussen (Eds). 2021. IOC World Bird List (v11.2). doi: 10.14344/IOC.ML.11.2.

Lepage, D., Vaidya, G., & Guralnick, R. (2014). Avibase – a database system for managing and organizing taxonomic concepts. ZooKeys, (420), 117.

Literatur und nützliche Links: Nützliche Links für Bilder, Videos und Vogelstimmen finden Sie hier: www.ebird.org und www.xenocanto.org

Ali, S., & Ripley, S. D. (1999). Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan: Together with those of Bangladesh, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan and Sri Lanka. 10 Volume Set (Vol 1-10). Oxford University Press.

Andreotti, A., Besa, M., Genovesi, P., & Guberti, V. (2001). Mammiferi e Uccelli esotici in Italia: analisi del fenomeno, impatto sulla biodiversità e linee guida gestionali. N. Baccetti, & A. Perfetti (Eds.). Ministero dell’ambiente, Servizio conservazione natura.

Anton, M., Herrando, S., Garcia, D., Ferrer, X. & Cebrian, R. (2017). Atles dels ocells nidificants de Barcelona. Ajuntament de Barcelona/ICO/UB/Zoo. Barcelona

Arnold, R., Woodward, I. and Smith, N. (2018). Parrots in the London Area – A London Bird Atlas Supplement. London Natural History Society

Baccetti, N., Spagnesi, M., & Zenatello, M. (1997). Storia Recente Delle Specie Ornitiche Introdotte In Italia. Suppl. Ric. Biol. Selvaggina 27: 299-316.

Baicich, P. J., & Harrison, C. J. 0. (2005). A guide to the nests, eggs, and nestlings of North American birds. Second Ediction. Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford.

Baker, J., Harvey, K. J., & French, K. (2014). Threats from introduced birds to native birds. Emu-Austral Ornithology, 114(1), 1-12.

Banks, A. N., Wright, L., Maclean, I. M., Hann, C., & Rehfisch, M. M. (2008). Review of the status of introduced non-native waterbird species in the area of the African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement: 2007 update. Norfolk, United Kingdom: British Trust for Ornithology.

Bauer, H. G., & Woog, F. (2008). Nichtheimische Vogelarten (Neozoen) in Deutschland, Teil I: Auftreten, Bestände und Status. Vogelwarte, 46(3), 157-194.

Bauer, H. G., Geiter, O., Homma, S., & Woog, F. (2016). Vogelneozoen in Deutschland–Revision der nationalen Statuseinstufungen. Vogelwarte, 54, 165-179.

Blackburn, T. M., & Duncan, R. P. (2001). Determinants of establishment success in introduced birds. Nature, 414(6860), 195-197.

Blackburn, T. M., Lockwood, J. L., & Cassey, P. (2009). Avian invasions: the ecology and evolution of exotic birds (Vol. 1). Oxford University Press.

Blackburn, T. M., Pyšek, P., Bacher, S., Carlton, J. T., Duncan, R. P., Jarošík, V., … & Richardson, D. M. (2011). A proposed unified framework for biological invasions. Trends in ecology & evolution, 26(7), 333-339.

Bon, M., Semenzato, M., Fracasso, G., & Marconato, E. (2008). Sintesi delle conoscenze sui Vertebrati alloctoni del Veneto. Boll. Mus. civ. St. nat. Venezia, 58, 37-64.

Borrow, N., & Demey, R. (2014). Birds of Western Africa. Helm Field Guides, London.

Carrete, M., & Tella, J. (2008). Wild‐bird trade and exotic invasions: a new link of conservation concern?. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 6(4), 207-211.

Cassey, P., Blackburn, T. M., Sol, D., Duncan, R. P., & Lockwood, J. L. (2004). Global patterns of introduction effort and establishment success in birds. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 271(suppl_6), S405-S408.

Cheke, A. (2019). A long-standing feral Indian Peafowl population in Oxfordshire, and a brief survey of the species in Britain. British Birds, 112, 337-348.

Chiron, F., Shirley, S., & Kark, S. (2009). Human-related processes drive the richness of exotic birds in Europe. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 276(1654), 47-53.

Clement, P. (1999). Finches and sparrows. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Cramp, S. & Perrins, C. M. (1994). The birds of the Western Palearctic. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Cucco, M., Alessandria, G., Bissacco, M., Carpegna, F., Fasola, M., Gagliardi, A., … & Pellegrino, I. (2021). The spreading of the invasive sacred ibis in Italy. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1-13.

De Juana, E., & Garcia, E. (2015). The birds of the Iberian Peninsula. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D. A., & de Juana, E. E. (2018). Handbook of the birds of the world alive. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions.

Dubois, P. J. (2007). Les oiseaux allochtones en France: statut et interactions avec les espèces indigènes. Ornithos, 14, 329–364.

Dubois, P. J., Maillard, J. F., & Cugnasse, J. M. (2016). Les populations d’oiseaux allochtones en France en 2015 (4 e enquête nationale). Ornithos, 23, 129-141.

Duncan, R. P., Blackburn, T. M., & Sol, D. (2003). The ecology of bird introductions. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 34(1), 71-98.

Dunn, J. L. & Alderfer, J. (2017). Field guide to the birds of North America. National Geographic Books.

Essl, F. & Rabitsch, W. (2002): Neobiota in Österreich. Umweltbundesamt, Wien, 432 pp.

Fox, A. D., Heldbjerg, H., & Nyegaard, T. (2017). Invasive alien birds in Denmark. Citizen Science Based Bird Population Studies, 187.

Frith, C. B. (2004). The Birds of Africa. Volume VII (Eds C. Hilary Fry and Stuart Keith). Christopher Helm, London.

Gibbs, D., Barnes, E., & Cox, J. (2010). Pigeons and doves: a guide to the Pigeons and doves of the world. London, UK: A&C Black Publishers

Global Biodiversity Information Facility: www.gbif.org

Hagemeijer, W. J., & Blair, M. J. (1997). The EBCC atlas of European breeding birds. Poyser, London, 479.

Harrison, C. J. O. & Castel, P. (2002). Field guide to the nests, eggs and nestlings of Britain and Europe. Collins.

Holling, M., & the Rare Breeding Birds Panel. (2017). Non-native breeding birds in the UK, 2012–14. Brit. Birds 110: 92–108

Hulme, P. E., Bacher, S., Kenis, M., Klotz, S., Kühn, I., Minchin, D., … & Vilà, M. (2008). Grasping at the routes of biological invasions: a framework for integrating pathways into policy. Journal of Applied Ecology, 45(2), 403-414.

iNaturalist: www.inaturalist.org

Institute of Nature Conservation PAS: www.iop.krakow.pl

Invasive Species in Belgium: http://ias.biodiversity.be/

Johnsgard, P. A. (1978). Ducks, geese, and swans of the world. – University of Nebraska Press, 1st edition, Lincoln, Nebraska

Keller, V., Herrando, S., Voříšek, P., Franch, M., Kipson, M., Milanesi, P., Martí, D., Anton, M., Klvaňová, A., Kalyakin, M.V., Bauer, H.-G. & Foppen, R.P.B. (2020): European Breeding Bird Atlas 2: Distribution, Abundance and Change. European Bird Census Council & Lynx Edictions. Barcelona

Kestenholz, M., Heer, L., & Keller, V. (2005). Etablierte Neozoen in der europäischen Vogelwelt–eine Übersicht. Ornithol. Beob, 102(3), 153-180.

Kumschick, S., & Nentwig, W. (2010). Some alien birds have as severe an impact as the most effectual alien mammals in Europe. Biological conservation, 143(11), 2757-2762.

Lensink, R., Ottens, G., & van der Have, T. (2013). Vreemde vogels in de Nederlandse vogelbevolking: een verhaal van vestiging en uitbreiding. Limosa, 86(2), 49-67.

Lever, C. (2005). Naturalised birds of the world. A&C Black.

Lukasiewicz, M., Matuszewski, A., Kamaszewski, M., & Wardecki, L. (2018). Selected invasive species of the Polish and European avifaunae. Annals of Warsaw University of Life Sciences-SGGW. Animal Science, 57.

Madge, S., McGowan, P. J., & Kirwan, G. M. (2002). Pheasants, partridges and grouse: a guide to the pheasants, partridges, quails, grouse, guineafowl, buttonquails and sandgrouse of the world. A&C Black

Matias, R. (2002). Aves exóticas que nidificam em Portugal continental. Instituto da Conservação da Natureza. Lisboa

Menkhorst, P., Rogers, D., Clarke, R., Davies, J., Marsack, P., & Franklin, K. (2017). The Australian bird guide. Csiro Publishing.

Mentil L., Battisti C. & Carpaneto G.M. (2018). The impact of Psittacula krameri (Scopoli, 1769) on orchards: first quantitative evidence for Southern Europe. Belgian Journal of Zoology 148 (2): 129–134.

Mlíkovský, J. & Stýblo P. (Eds.) (2006): Nepůvodní druhy fauny a flóry České republiky. Praha: ČSOP.

Mori, E., Grandi, G., Menchetti, M.,Tella, J. L., Jackson, H. A., Reino, L., van Kleunen, A., Figueira, R. & Ancillotto, L. (2017). Worldwide distribution of non–native Amazon parrots and temporal trends of their global trade. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation, 40.1: 49–62.

National Biodiversity Network Atlas: https://records.nbnatlas.org

Naturbasen – Danmarks National Artsportal: https://www.naturbasen.dk/

Nehring, S., Rabitsch, W., Kowarik, I., & Essl, F. (Eds.). (2015). Naturschutzfachliche Invasivitätsbewertungen für in Deutschland wild lebende gebietsfremde Wirbeltiere. Bundesamt für Naturschutz.

Nikolov, B., Kralj, J., Legakis, A., Saveljic, D. & Velevski, M. (2016). Review of the alien bird species recorded on the Balkan Peninsula. In: Rat M., T. Trichkova, R. Scalera, R. Tomov, A. Uludag (Eds.), First ESENIAS Report: State of the Art of Invasive Alien Species in South-Eastern Europe. Publishers: UNS PMF, Novi Sad, Serbia, IBER-BAS, Sofia, Bulgaria, ESENIAS, ISBN:978-86-7031-3316, 189-201

Norwegian Biodiversity Information Centre (2018). The Alien Species List of Norway – ecological risk assessment 2018. https://www.biodiversity.no/alien-species-2018

Nowakowski, J. J., & Dulisz, B. (2019). The Red-vented Bulbul Pycnonotus cafer (Linnaeus, 1766)–a new invasive bird species breeding in Europe. BioInvasions Records, 8(4), 947-952.

Ornitho France: www.Ornitho.fr

Ornitho Italia: www.ornitho.it

Ottens, G., & Ryall, C. (2003). House crows in the Netherlands and Europe. Dutch Birding, 25, 312-319.

Pagani–Núñez, E., Renom, M., Furquet, C., Rodríguez, J., Llimona, F., & Senar, J. C. (2018). Isotopic niche overlap between the invasive leiothrix and potential native competitors. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation, 41(2), 427-434.

Parr, M., & Juniper, T. (2010). Parrots: a guide to parrots of the world. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Pereira, P. F., Barbosa, A. M., Godinho, C., Salgueiro, P. A., Silva, R. R., & Lourenço, R. (2020). The spread of the red-billed leiothrix (Leiothrix lutea) in Europe: The conquest by an overlooked invader?. Biological Invasions, 22(2), 709-722.

Pereira, P. F., Godinho, C., Vila-Viçosa, M. J., Mota, P. G., & Lourenço, R. (2017). Competitive advantages of the red-billed leiothrix (Leiothrix lutea) invading a passerine community in Europe. Biological Invasions, 19(5), 1421-1430.

Pereira, P. F., Lourenço, R., & Mota, P. G. (2018). Behavioural dominance of the invasive red-billed leiothrix (Leiothrix lutea) over European native passerine-birds in a feeding context. Behaviour, 155(1), 55-67.

Pereira, P. F., Lourenço, R., & Mota, P. G. (2020). Two songbird species show subordinate responses to simulated territorial intrusions of an exotic competitor. acta ethologica, 23(3), 143-154.

Poole, K. (2010). Bird introductions. Extinctions and Invasions: a social history of British fauna, 155-165.

Ramellini, S., Simoncini, A., Ficetola, G. F., & Falaschi, M. (2019). Modelling the potential spread of the Red-billed Leiothrix Leiothrix lutea in Italy. Bird Study, 66(4), 550-560.

Rasmussen, P. C., & Anderton, J. C. (2012). Birds of south Asia. The Ripley Guide. Vols. 1 and 2. Second Edition. National Museum of Natural History – Smithsonian institution, Michigan State University and Lynx Edictions, Washington, D.C., Michigan and Barcelona.

Robson, C. (2008). A field guide to the birds of South-east Asia. London, UK: New Holland Publishers Ltd.

Sanz-Aguilar, A., Anadón, J.D., Edelaar, P., Carrete, M. & Tella, J.L. (2014). Can Establishment Success Be Determined through Demographic Parameters? A Case Study on Five Introduced Bird Species. PLoS ONE 9(10): e110019. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0110019

Senar, J. C., Carrillo-Ortiz, J. G., Ortega-Segalerva, A., Dawson Pell, F. S. E., Pascual, J., Arroyo, L., … & Hatchwell, B. J. (2019). The reproductive capacity of Monk Parakeets Myiopsitta monachus is higher in their invasive range. Bird Study, 66(1), 136-140.

Sibley, D.A. (2014). The North American Bird Guide. 2nd Edition. Bloomsbury, New York.

Sol, D., Bartomeus, I., & Griffin, A. S. (2012). The paradox of invasion in birds: competitive superiority or ecological opportunism?. Oecologia, 169(2), 553-564.

Sol, D., Timmermans, S., & Lefebvre, L. (2002). Behavioural flexibility and invasion success in birds. Animal behaviour, 63(3), 495-502.

Species Obseration System – SLU Artdatabanken: https://www.artportalen.se/

Šťastný, K. (2018). Nepůvodní ptáci ve fauně České republiky. Živa 5/2018: 272-276.

Svensson, L., Mullarney, K., & Zetterström, D. (2010). Collins bird guide 2nd edition. British Birds, 103, 248-252.

UNEP-WCMC. 2015. Update on the status of non-native waterbird species within the AEWA Area. Cambridge: UNEP-WCMC

Vall-llosera, M., Llimona, F., de Cáceres, M., Sales, S., & Sol, D. (2016). Competition, niche opportunities and the successful invasion of natural habitats. Biological invasions, 18(12), 3535-3546.

Vavřík M., Šírek J., Šindel M., Mlíkovský J., Horáček J., Heyrovský D. & Šimek J. 2019: Revize záznamů vzácných druhů ptáků v České republice. Sylvia 55: 2–74.

Waarneming: https://waarneming.nl

Waarnemingen: https://waarnemingen.be

White, R. L., Strubbe, D., Dallimer, M., Davies, Z. G., Davis, A. J., Edelaar, P., … & Shwartz, A. (2019). Assessing the ecological and societal impacts of alien parrots in Europe using a transparent and inclusive evidence-mapping scheme. NeoBiota, 48, 45.

Yésou, P. & Clergeau, P. (2005). Sacred Ibis: a new invasive species in Europe. Birding World 18 (12): 517-526.

Mitwirkende und Finanzierung

Forschungsgruppe (University of Évora, Portugal):

Pedro Filipe Pereira

Carlos Godinho

Inês Roque

João Eduardo Rabaça

Rui Lourenço

Mitwirkende:

Ana Diniz Sampaio, University of Évora

David Epple, Technical University of Munich

Elsa Leclerc Duarte, University of Évora

Fer Goytre, Fotografía de Naturaleza

Francesco Valerio, University of Évora

Hany Alonso, Portuguese Society for the Study of Birds (SPEA)

Pedro Alexandre Salgueiro, University of Évora

Pedro Almeida, University of Évora

Teresa Gomes, University of Évora

Abbildungen:

Pedro Filipe Pereira

Fotos:

Alessandro Mariani, Italia; Leiothrix lutea und Parus major

Carlos Santos, Alapraia, Portugal; Acridotheres cristatellus singendes Vogel

Carlos Sarabia, Fotografía de Naturaleza, España; Pycnonotus jocosus

Carole Philippon, France, Instagram: @carole.nature.photos; Umfrage: Leiothrix lutea und Erithacus rubecula

Christian Almendro, España, Instagram: @kostripadventure; Pavo cristatus Balz

Elena Giuffra, Italia, Instagram: @elena.giuffra; 2 Leiothrix lutea fütterung

Eva M Sánchez-Flores, España, Instagram: @evalynxphotograph; Estrilda astrild fütterung

Fátima Mendes, Portugal; Acridotheres cristatellus und Pferd

Francisco Santos, Portugal; Estrilda astrild junge fütternd

Hawi Grömping, Germany, www.naturschule.com; Umfrage: Phoenicopterus chilensis und Phoenicopterus roseus

Jean Yves Paquereau, photographie de la nature, France; Threskiornis aethiopicus

João Lelo, Portugal, Instagram: @joaolelophotography; Ploceus melanocephalus

Mala Patel, Director The Caketail Club, England, the United Kingdom; 2 Psittacula krameri

Mar López, Fotografía de Naturaleza, Alcalá de Henares, España; Myiopsitta monachus fütterung

Mari Carmen López Luengo, España, Instagram: @mcarmen_photography; Myiopsitta monachus und Columba livia

Paul Abrahams, the United Kingdom, www.gingerwildlifephotography.co.uk; Branta canadensis und Anser anser; Branta canadensis und Cygnus olor

Pedro Filipe Pereira, University of Évora, Portugal; Pavo cristatus brütendem

Peter Koenis, the Netherlands; Cygnus atratus und Cygnus olor

Philip John Passey, England, the United Kingdom; Psittacula krameri und Corvus monedula

Samuele Ramellini, University of Milan, Italy; Leiothrix lutea paar; 1 Leiothrix lutea fütterung

Saskia Lemmens, Sayly Photography, the Netherlands; Alopochen aegyptiaca und Ciconia ciconia

Teresa Palacios, Fotógrafa, España, www.teresapalacios.es; Phasianus colchicus Balz

Ton Petrus, the Netherlands; Psittacula krameri fütterung

Vie Schoen, the Netherlands; Phoenicopterus chilensis Paarung

William Atkinson, Mid-Wales, the United Kingdom; Phasianus colchicus Kampf

Finanzierung:

MED (IUPB/05183/2020) – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia

Kontakte:

LabOr – Laboratory of Ornithology

MED – Mediterranean Institute for Agriculture, Environment and Development

Instituto de Investigação e Formação Avançada

Universidade de Évora, Pólo da Mitra, Ap. 94, 7006-554 Évora, Portugal

Telefon: 00351 266 760 897

E-mail: labor@uevora.pt

Research Team (University of Évora, Portugal)

Carlos Godinho

Inês Roque

João Eduardo Rabaça

Pedro Filipe Pereira

Rui Lourenço

Vögel zeigten Brutverhalten

Nilgans (Alopochen aegyptiaca) – Konkurrenz um Nistplätze / aggressives Verhalten: von der exotischen Art gegenüber einem anderen Tier (Weißstorch – Ciconia ciconia)

Jagdfasan (Phasianus colchicus) – Territoriales Verhalten (Kampf) / aggressives Verhalten: zwischen Individuen der exotischen Art

Vögel zeigten andere Verhaltensweisen

Sonnenvogel (Leiothrix lutea) – Fraß: Landwirtschaftliche Nutzpflanzen (kaki)

Wellenastrild (Estrilda astrild) – Fraß: wilde Pflanzen (Binsen Samen)

Halsbandsittich (Psittacula krameri) – Fraß: vogelfutter / aggressives Verhalten: zwischen Individuen der exotischen Art

Sonnenvogel (Leiothrix lutea) – Fraß: Landwirtschaftliche Nutzpflanzen (Kaki) / aggressives Verhalten: von der exotischen Art gegenüber einem anderen Tier (Kohlmeise – Parus major)

Halsbandsittich (Psittacula krameri) – Fraß: Zierpflanzen (Kirschblüten)

Kanadagans (Branta canadensis) – schwimmt / aggressives Verhalten: von der exotischen Art gegenüber einem anderen Tier (Graugans – Anser anser)

Kanadagans (Branta canadensis) – schwimmt / aggressives Verhalten: von einem anderen Tier (Höckerschwan – Cygnus olor) gegenüber der exotischen Art

Schwarzschwan (Cygnus atratus) – schwimmt / aggressives Verhalten: von der exotischen Art gegenüber einem anderen Tier (Höckerschwan – Cygnus olor)

Mönchssittich (Myiopsitta monachus) – Soziales Verhalten: die exotische Art hat mit anderen Tieren interagiert (Straßentaube – Columba livia), aber ohne aggressives Verhalten zu zeigen

Haubenmania (Acridotheres cristatellus) – Soziales Verhalten: die exotische Art hat mit anderen Tieren interagiert (Pferd), aber ohne aggressives Verhalten zu zeigen